Babka

My most prized possession during my fractured childhood was a red plastic transistor radio that I religiously kept tuned to 1010 WINS news. “You give us 22 minutes, we’ll give you the world,” was a promise that minute by minute and hour by hour helped me maneuver through a landscape of childhood strife. In 22 minutes, a war might break out. A three-car accident might close inbound traffic lanes on the Brooklyn Bridge.

When the anxiety became too much for me to handle, I would be packed off to spend the weekend with a Hasidic family in Borough Park or Crown Heights, where parents never fought and children came downstairs freshly washed and dressed for Friday night dinner. There, I never needed my radio. The families who lived in the solid, modest brick houses were warm and accepting, and they took care of each other. They took me to see their Rebbes, each of whom incarnated a different and wondrous style of spiritual kung fu. The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s unearthly blue eyes could penetrate to your inner soul with a single glance and see everything there was to see there. The Bobover Rebbe was joyous and funny, and his Hasidim were, too. Together, they sang for hours, until their wordless melodies broke open the doors of heaven. The Belzer Rebbe was nice, too.

What these Rebbes shared in common with me was that we had all, in different ways, been touched by God. Finding a way to express that feeling was the work of a lifetime, which perhaps only a holy person could accomplish. But what about the Satmar Rebbe? It was said that Rebbe Yoel was a great tsadik, who pursued stringencies that even the Lubavitcher Rebbe, himself a titan, could never have handled, like waiting 24 hours to eat dairy after meat, perhaps, or fasting for the entire week of Tisha B’Av.

When I got older, I learned that Rebbe Yoel’s pursuit of extreme stringencies had led him to board a train to Switzerland at the darkest hour of Jewish history after forbidding members of his community from saving themselves. Better to die, he told them, than to travel to Palestine or America and lose your faith in such godless places. Even today, the story of Rebbe Yoel makes me feel a mixture of fury and helplessness that I associate with being a frightened child, clutching my little radio. There was nothing good about the secrets that the Satmar were keeping.

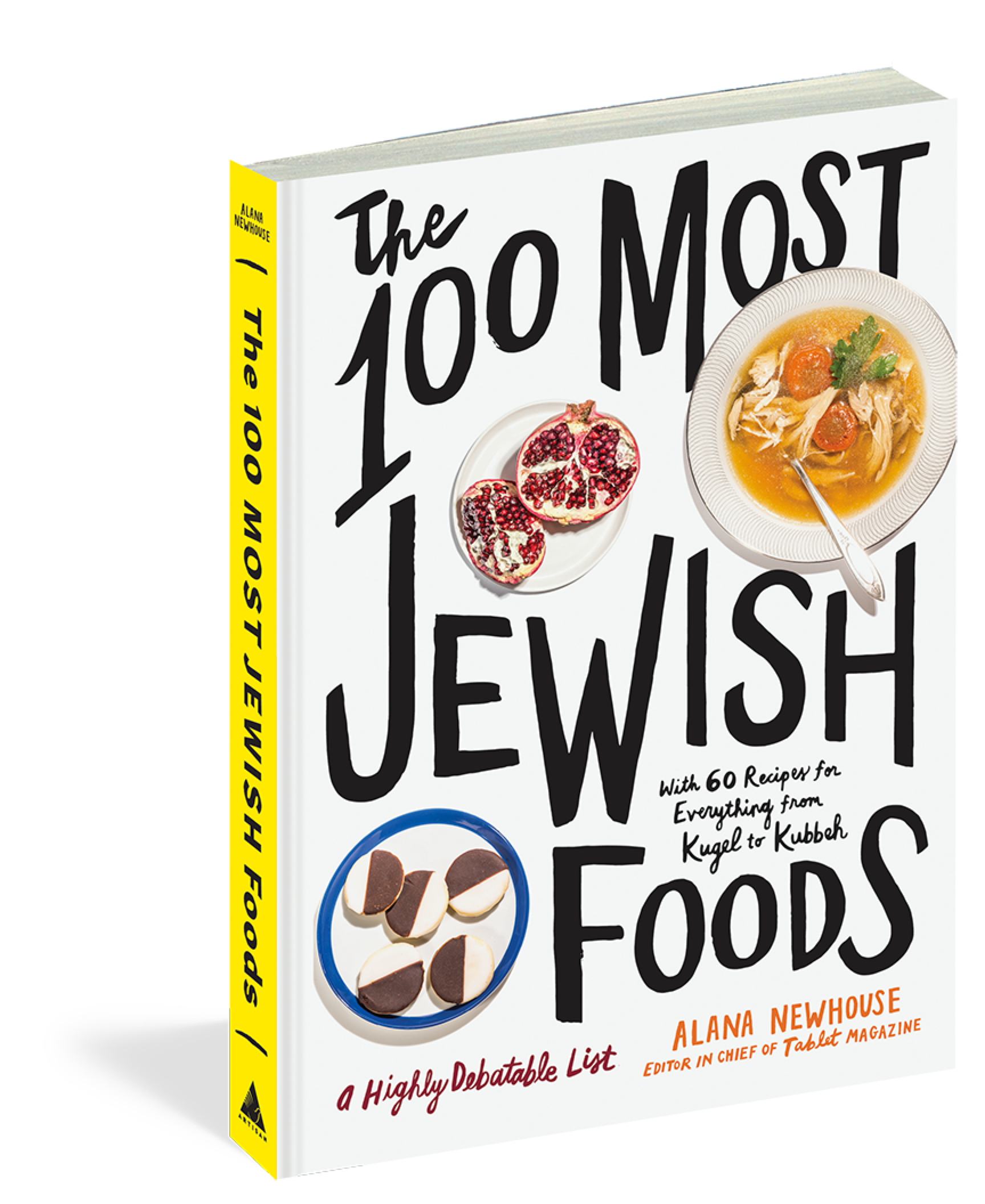

Except, I was wrong. When my first son was born, I needed something to serve guests at his bris, and I ventured down to Lee Avenue in Williamsburg, where I discovered the greatest chocolate babka in the world, a tall brioche filled with swirls of moist chocolate lava, which dries on the outside into an impossibly delicious crust. It is available at the Oneg Heimishe Bakery, which goes by other names, and is located just below street level, right across the highway. If you are looking for it, you will find it. And if not, not.

David Samuels, Tablet’s literary editor, is a contributing editor at Harper’s Magazine and a longtime contributor to The Atlantic and The New Yorker.