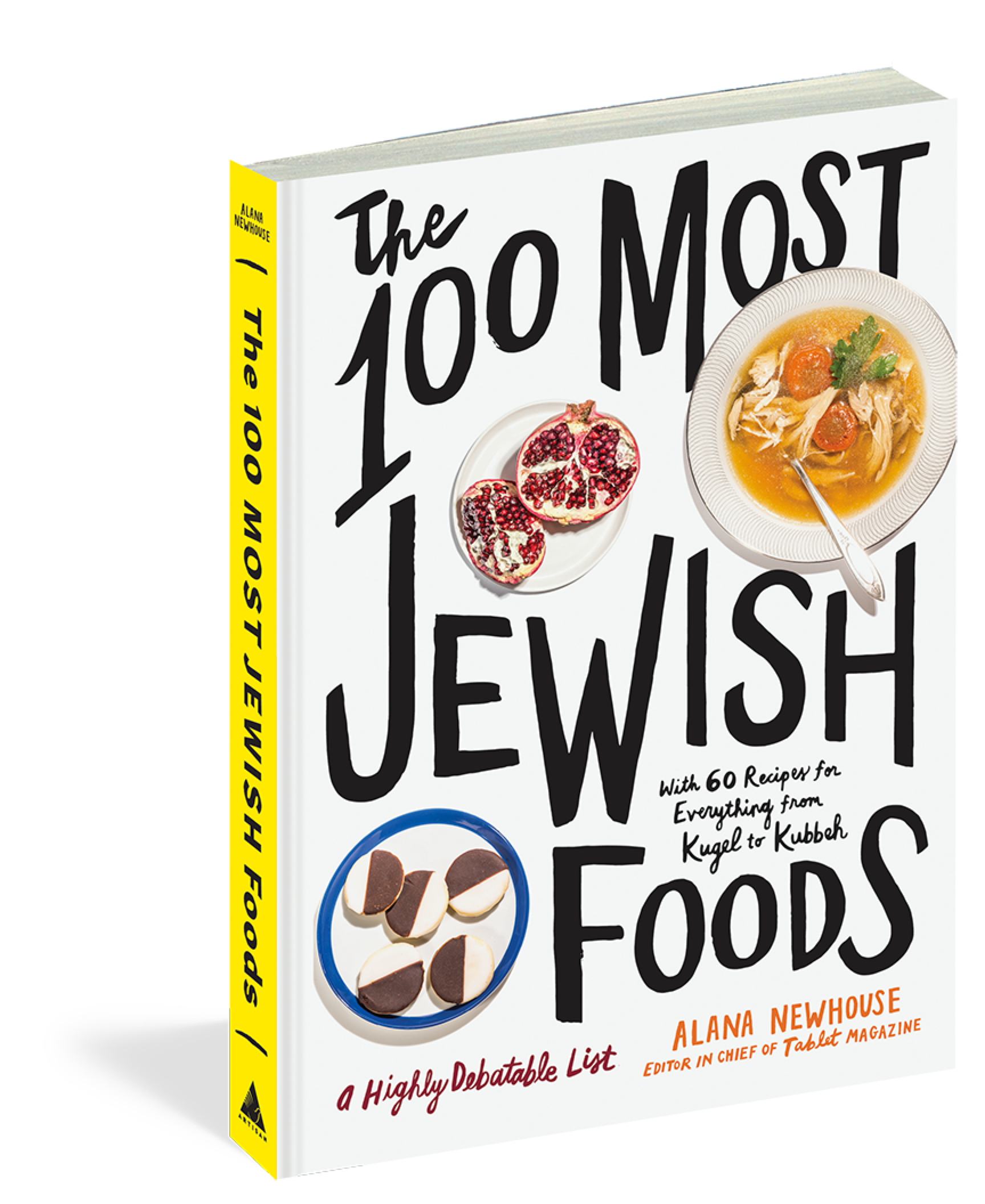

Black-and-White Cookies

Long before Jerry Seinfeld and President Obama declared black-and-white cookies to be an edible symbol of racial harmony, these chocolate and vanilla confections were simply a treat my grandmother Ella picked up at our local kosher bakery in Flatbush, along with the mandelbrot and babka. Maybe it was your cousin Rose who got them on the Upper West Side, or your great Uncle Harry in the Bronx. They were all around the city.

Black-and-whites have been an entrenched part of the very robust Jewish cookie scene in New York City for a century. More ubiquitous than rugelach, they are available in bodegas and bagel shops, where they remain as popular as ever.

They didn’t necessarily start out as Jewish. Originally from Bavaria, they came to the United States with German immigrants—maybe Jewish, maybe not. Some sources state they began their American sojourn on the Lower East Side; others point to Utica, N.Y. Versions of the cookie exist across the Northeast and Midwest, where they go by different names (half-moons, harlequins). The recipe is changeable as well. In some places, they’re made from devil’s food cake and soft buttercream instead of the lemon-scented sponge cake shellacked with the hardened chocolate and vanilla glazes I knew as a child. Other places use shortbread cookies and fondant.

But wherever or however they’re made, their common ground is chocolate and vanilla coexisting on a smooth, sweet surface. They’ve adapted to their surroundings without losing their essence, just like the Jews (and many other American immigrants for that matter). And like bagels, Chinese food, and Jerry Seinfeld, they’re a deep-rooted part of the New York Jewish experience—no matter where you might have experienced them.

Melissa Clark is a food columnist for The New York Times and the author of Dinner: Changing the Game.